A basic flight simulator tutorial

Foreword

Aviation is about extremes:

- An airplane is

quite fragile and flies at huge speeds. Yet it is one of the most

secure

transport devices.

- A pilot constantly follows

rules and

procedures. Yet an airplane is a symbol of freedom.

- Once you are

trained, flying a little airplane is easy. Yet if a problem occurs,

you have to sort of solve a rubicube in a few seconds.

- Many flight tutorials are

written with a lot of humor. Yet

an attempt

to make humor or show your skills with a real aircraft will bring you

before a court.

This tutorial is based on the Cessna 172p, which

is the default airplane on lots of flight simulators and a great

airplane:

Possibly take a quick look at the following articles. You may feel the

need to

come back to them later. They contain answers to questions that

can arise while reading this tutorial. The first ones show the

airplane's main parts and controls:

Hardware

I assume you are using the regular mouse and keyboard of your

computer. You need no joystick nor plastic pedals or control yoke to

use the

flight

simulator. Such hardware would be more realistic

(especially with force feedback). Yet I don't own any myself

and I

suppose most flight simulation candidates don't.

You need a "3D-accelerated graphics card" inside your

computer and its proper drivers installed. Don't bother if you don't

know what this is. Today most computers are sold with such a graphics

card. Simply install the flight simulator software and start it to

check you get a fluent display. If not, either an 3D-accelerated

graphics card isn't installed or its drivers aren't properly installed.

Get help.

Sound is not mandatory but it really helps. For example when landing

you need to hear the wheels touch the runway. Sound is one of the

direct neural connections that allow a pilot to become the airplane's

brain.

Software

To know the trim position, use the HUD (h,

H and I) or the I-shaped indicator on the

schematic instrument panel

(P).

The trim movement is very slow. Be patient.

Lots of modern airplanes have a remote control for the trim: a little

switch on the yoke, that you can manipulate easily with your fingers.

So you don't have to duck to roll the big wheel.

What direction am I flying?

Four basic methods exist to know what direction you are flying:

- Look through the windows.

Try to learn and recognize all

sorts of ground features, like hills, bridges, cities, forests... The

Sun and the Moon are essential features, but clouds can cover them and

they move through the sky. Looking through the windows can be quite

hectic on a flight

simulator. You only have a narrow view on the virtual outside world.

Using two more displays, placed left and right of the main one, will

help. Yet this is expensive and not mandatory. Several ways exist to

allow you to pan your virtual head inside the airplane:

- Use Shift and the four

arrow keys to

look frontwards, backwards,

leftwards and rightwards.

- Use Shift and the

keypad

keys to look in the four

directions mentioned above and in four diagonal directions in-between.

- Put the mouse in pan

mode (right button, <-|->

cursor look). This allows

you to look in just every direction, including towards the sky and

towards

the ground. This method is great while the autopilot is on. It is

a little dangerous otherwise, because the plane will bank or fall while

you're looking all around. Click the left mouse button to quickly get

back to the default forwards vision. Hint: if you click the left mouse

button to center the vision back, by the time you click the right mouse

button to go out of mouse look mode you will already have panned a few

degrees away from the forward view. This is not a serious problem,

except for the fact it prevents the instrument panel to appear when

typing P. A

solution is to

lift the mouse before you click the left button. Then click the right

button. Then let the mouse back down. (While the autopilot is on

and you are looking all around, use the x, X

and Ctrl-x keys to zoom in

and out. Use the z, Z

and Ctrl-z keys to dissolve

the mist outside.)

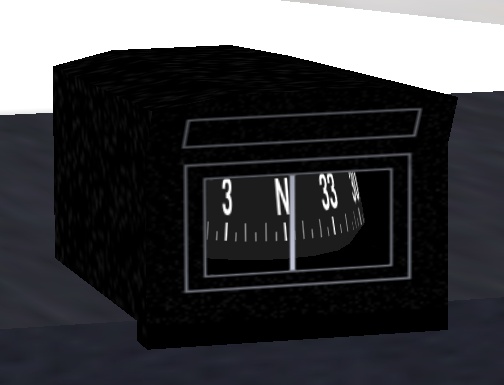

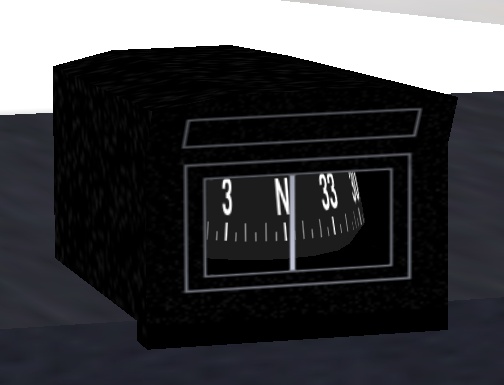

- The compass

(picture

below). This is the indicator located

above the

instrument panel. The compass is a very simple and classical, yet not

perfectly reliable instrument. When flying over some places, magnetic

perturbations on the ground can make the compass tell nonsense. Also,

the compass never shows the real direction of the North, East or South.

Rather it shows a direction a few degrees aside from the real direction

(depending on the country you are in). Close to the poles the error of

the compass becomes really strong.

- The directional

gyro

(picture below) or "heading indicator". The gyro is started before

take off and keeps its

initial heading for hours. It simply tells you how many degrees you

turned to the left or to the right. You are supposed to tune in the

right direction of the North Pole before you take off, using the knob

at the bottom left of the instrument (normal mouse pointer mode, click

left or

right

half of the knob, middle mouse button to move faster, Ctrl-c

to highlight halves). (The red knob, bottom right, is used to tell the

autopilot what direction you wish to fly (HDG

= "heading").

- The clock. If you make

steady turns, at the angle proposed

by the turn indicator, a 180° turn takes 60 seconds whatever

the flight

speed (yet it is 50 seconds on FlightGear...).

!

During a real flight in

a

real

airplane, you

are supposed to cross-check all direction indicators once in a while.

Memorize the directions: North is 0°, East is

90°, South is 180° and West is 270°.

A realistic take off

By now I assume you are able to keep the airplane on the runway while

taking off (rudder) and you're able to fly straight, descend

peacefully, gain altitude steadily, make gentle turns (yoke)... No need

you perform this all perfectly. Yet a basic and approximate control of

the airplane has been acquired.

Rules during take off:

- You are not allowed to keep

the front wheel on the ground

above 40 knots. It would shimmy.

- When close to the ground (I don't know the exact limit) you have

to keep the two rear wheels at the same height above the runway. The

reason is any moment you will or may touch the ground. You need to

touch with both two rear wheels together. That means you need to keep

the

wings level with the horizon. Hence you cannot make use of the

yoke/mouse/ailerons to turn. Instead you use the rudder pedals to turn.

(Since you fly around 70 knots, this yields not too much sideways

force problems.) The yoke/mouse/ailerons are used to keep the wings

level with the horizon.

- You are not allowed to fly lower than 500 feet above the ground.

The sole exception is in the axis of the runway, during take off and

during landing. (While flying over cities you are not allowed to fly

lower than 1,000 feet above the ground.)

- When lower than 500 feet above the ground, you are not allowed to

fly slower than 70

knots speed.

That's because a blow of wind from the rear can occur any moment. You

need to fly fast enough so that such wind blows won't make the plane

stall and fall to

the

ground.

- When lower than 500 feet (above the ground),

you are not allowed to fly much

faster

than 70

knots. You

wouldn't be able to make maneuvers quick enough. You would be more

destructive if you hit something. Besides, 70 knots is a nearly optimal

speed to gain altitude and your sole acceptable purpose while lower

than 500 feet is to gain altitude...

- While taking off, you must stay aligned with the

runway. Indeed that's the sole place you are allowed to fly below 500

feet. (If you take off from a long runway like KSFO, this also allows

to land back safely and quickly should an emergency occur. (Above a

short runway, you

cannot simply dive and get back on the runway, because it is too short.

You need to turn and circuit to make a regular landing. For this you

need to have enough engine power or to be at least at 500

feet above

the ground. Otherwise, quickly find a place where you can make an

emergency landing.))

So, you need to take off and rise in the

air at a steady speed

of around 75 knots.

Problem: since the front wheel is slightly lifted and the flaps are one

step

deployed, the plane will rise from the ground already at 55 knots.

That's well below the desired flight speed of 75 knots. What to do

then?

Answer: as soon the two rear wheels lift from the ground,

push the yoke forwards a little. Keep the plane close above the

ground. (The aim of this is: should a wind blow from the rear occur,

the plane will fall from only a few feet hight.) (Please do not train

to keep the plane exactly two

feet above the ground. Doing so would be dangerous. Do allow the plane

to rise slightly while it accelerates, but, simply put: do not favor

this tendency.) So, keep it close

above the

ground while accelerating, till a speed of about 70 knots is reached.

Then switch to the opposite mode: now you must pull on the yoke to

prevent the plane from going above 75 knots. Force the plane to

rise in the air, so it doesn't gain speed. Keep in control. If the

speed goes below 75 knots, push a little on the yoke. If it rises above

75 knots, pull a little on the yoke. Till you reach 500 feet above the

ground.

This is the procedure I use to take off. I assume you just started

FlightGear; the airplane is at the start of the runway and the engine

is turning at minimum power:

- Get a HUD (h, H, i

and I) or the schematic

instrument panel with the I indicator (2D panel aircraft from start or

key P).

- Deploy one step of flaps (]).

- Get in mouse yoke mode (+

pointer shape) by clicking on the right mouse button.

- Pull the yoke/mouse/elevator to 1/2 the total way:

- Ensure the yoke/mouse/ailerons is centered:

- Push the left mouse button down and keep it down, so the mouse

gets in rudder control mode. (If you don't want to use the mouse to

control the rudder, use the keypad 0

and Enter keys.) (Before you

push the left mouse button, ensure the yoke/elevator is pulled 1/2 like

asked above and the yoke/ailerons is centered.)

- Keep the Page Up key

down till the engine roars at its maximum

power.

- The airplane is now accelerating. Move the rudder/mouse to the

left and to the right to keep aligned with the runway (the left button

is pressed). You need to keep

in the middle of the runway but this does not need to be very precise.

More important is your path is parallel with the runway middle line and

stable.

- Because the yoke/elevator is pulled 1/2 in, around 40 knots the

nose will rise up. Immediately release the left mouse button, to get

back in yoke control mode. Immediately push the yoke/mouse a little

bit, to keep the engine cover

below the horizon. You just need to let the front wheel rise a little

bit above the runway. Let the rudder keep its angle (probably slightly

turned to the right; two keypad Enter

hits from the center position). From now on keep the left mouse button

released,

to stay in yoke control mode. Use the keypad 0 and Enter keys to control the rudder.

(You can also make short presses on the left mouse

button to make little rudder adjustments. I prefer using the keys.)

- The airplane soon leaves the ground. The two rear wheels no

longer

touch the runway. Push the mouse a little, to prevent the airplane from

rising in the air. Keep it flying close above the runway and aligned

with

it. Well, do not try to stick really close to the ground... this would

be

dangerous. Do allow the plane to rise a little bit. Just do not favor

the

rising... Simply keep in mind your aim is to accelerate and not to gain

altitude. (Due to a mistake and/or an emergency situation (engine

failure, gust of wind, sudden obstacle...), some pilots have had the

bad reflex to pull on the yoke during this early part of the take off.

This resulted in a stall and the plane falling to the ground at high

speed... The consequences were often extreme.)

- Use the yoke/ailerons/mouse to keep the wings level with the

horizon. Use the rudder/keypad 0

and Enter to turn (needs

training). Optimal rudder position seems to be slightly right from

neutral; two keypad Enter

hits. Only slow and slight rudder tunings should be needed, maybe no

tuning at all.

- Once the airspeed reaches 70 knots, pull on the yoke/mouse a

little bit. Now

the airplane firmly rises in the air. If the speed gets below 75

knots,

push the yoke to force the airplane to rise slower and gain airspeed.

If the speed rises above 75, pull the yoke to rise faster and decrease

the airspeed. There is no need to be very precise. Try to keep a stable

speed. Just avoid to go below 70 knots and above 80 knots.

- Don't keep your eyes too much on the speed indicator while you

are

rising above the runway. Rather look at the horizon and at the engine

cover. The top of the engine cover should roughly match with the

horizon

line:

- If you want to check the position of the runway but you can't see

it

because it is hidden by the engine cover, push the yoke/mouse a short

while to make the nose dive a little bit for a second. This only works

for long runways. Another trick is to look for a building, a hill or

something far in

front of the runway, on the horizon. Keep aiming at that object while

rising in the air. Keep the engine cover a little below the horizon

line, so the object you aim at stays visible.

- Once you reach 500 feet, retract the flaps ([) and push the yoke

a little. Center the rudder (slowly, one step at a time). You are now

allowed to gain speed or go on climbing (your

choice, or the control tower's). Decrease the

engine power a little so the

RPM needle keeps in the green zone (Page

Down). Turn calmly

towards your intended

flight direction. Use your time to optimize the mixture. You're in

flight.

500 feet above the ground is the minimum flight altitude above open

land. Above a

city the

minimum altitude is 1,000 feet.

If you take off from KSFO heading to the West, you have city areas in

front of you and left of you. So, once you reach 500 feet above the

ground, best turn to the right.

Don't forget to center the rudder. If the rudder is pushed to

one side, this will brake the plane. It makes the plane move

sideways through the air, with its flank aerobraking.

Don't forget to retract the flaps.

!

During a real take off

you

must keep in

touch with

the control tower. You also have to constantly look in all directions

to check no other airplane is coming in your direction.

An aviation classic is the ground effect.

It's the fact a wing lifts

better when close above to the ground. That too makes the wheels leave

the ground at quite a low speed, a speed at which the airplane cannot

really fly. While you are accelerating a few feet above the runway,

you are in ground effect. If you know about it, ground effect is an

advantage because it makes flying close above the ground more secure.

The airplane behaves a tiny little bit like a hovercraft. If you are

not aware of the ground effect, it can cause problems. For example it

can make you think the airplane has enough speed to rise in the

air, while it has not.

!

During a real take off, if the engine halts below 500 feet, you are not

allowed to turn and try to glide and land back on the runway. You only

have

enough height to try to turn and land back if you are above 500 feet

when the

engine halts.

! Before a real

take off you have to go through check-lists. A checklists makes you

verify, tune and tighten a list of items. You have to follow a long

checklist

before you enter the runway and a short checklist before you

accelerate to take off.

This is the checklist I follow when I take of the virtual Cessna 172p

on FlightGear. It is very short compared to a real checklist. Anyway I

know I can go into (moderate) trouble if I don't follow it. I had to

build up the discipline to follow it carefully each time:

- Check the wind direction.

- Deploy one step of flaps.

- Click the right mouse button and ensure the mouse is in yoke mode

(+).

- Put on a HUD (h, H, i,

I) or the schematic

instrument panel (P) in order

to know the controls positions.

- Pull the yoke/mouse to 1/2 the pull path.

- Check the yoke/ailerons are centered.

- Keep the left mouse button down and check the rudder is centered

or slightly to the right.

- Keep the Page Up button

down to start accelerating, till the engine RPM is maximum.

Landing

When I was a boy, I had a simple yet fairly good flight simulator on my

Sinclair ZX Spectrum

home computer. I could do everything with it, except

landing. I always crashed the plane, or reached the end of the runway

before stopping.

One day a real pilot saw me trying to land. He had never seen a flight

simulator, but he had no problem to recognize each flight instrument

and ground feature on the screen. He told me what to do. Decrease

engine power, increase engine power, push the nose down, pull the nose

up, turn a little left, turn a little right, get the flaps out... We

made a perfect landing on the second attempt.

Just like for take off, landing

is partly a procedure, partly rules you

have to stick to. You have to adapt constantly.

Same basic rules apply as for take off, yet in reverse order:

- Stay at 70 knots once below

500 feet. Descend towards the runway while

keeping at 70 knots.

- After the final rounding (see below), stay close above the runway

while decreasing speed from

the

70 knots flight speed down to the roughly 55 knots landing speed.

- Touch the runway

with the two main wheels. Keep

the front

wheel from the ground till the speed is below 40 knots.

(If you know what you are doing you are allowed to use a speed a little

below 70 knots: 65 knots.)

Following rules are essential during the

whole procedure of landing:

- Tune the speed using the

yoke/mouse/elevator: push the yoke if you are

flying

below 70 knots, pull the yoke if you are flying above 70 knots.

No

matter this makes you gain or lose altitude (except when this causes a

danger of course).

- Tune the altitude using the

engine throttle. Add power if

you are too low, retract power if you are too high.

- Once approaching the ground,

use the yoke/ailerons to keep the wings

level with the horizon. Turn using the rudder.

- Don't shut the engine down. Only shut the engine down when the

airplane is completely halted on the ground. There are two reasons for

this:

- Any moment you may need full engine power to rise back in the

air.

- Engine thrust enables you to make more precise landings. For

example if you land on a very short runway, you need that precision.

The reason why the yoke/elevator is used to tune

the speed is this method

allows for fast reactions and fine tuning. It is more important to tune

the speed closely than the altitude.

If you are both a little too high and a little

too slow, simply push the yoke a little and both problems will be

solved together. No need to use the throttle. Use your mind...

You have to get aligned with the runway. That means your flight

direction has to match the middle line of the runway (drawing (a)

below). In order to arrive at this, don't aim at the start of the

runway (b).

Rather aim at a fictitious point well ahead of the runway (c). And

begin

to turn gently towards the runway well before you reach that fictitious

point (d). Note the turns and bankings you make for these flight

corrections are often very soft. You wouldn't even notice them on the

turn coordinator. This is one example where you better rely on the

outside horizon line than on the inside flight instruments.

Try to get aligned with the runway as soon as possible. Constantly

apply the alignment procedure. The closer you come to the runway, the

better the alignment should become. At tip: if you see that the two

sides of the runway form an equal angle towards you, like / \ , this

means you are above the middle line of the runway (supposing that

middle line extends in front of the runway). So, if you see the runway

neatly / \ and it is perfectly in front of you; in the middle of your

flight direction; everything's fine. But if the runway is neatly / \

and it is situated to the right or to the left, this means you should

have turned earlier to align. Now you sure are above the middle line

extending from the runway, but you are flying in a wrong direction,

away from that middle line and from the runway start...

My favorite landing procedure for the Cessna 172p is roughly this one:

- Far from the runway, yet

already heading towards it,

start decreasing the

speed and let the plane descend towards 500 feet.

- Check the rudder is neutral.

Otherwise the plane will be braking and more engine power is needed.

(Type keypad keys 0 and Enter to center the rudder if

needed.) If you make corrections using the rudder, keep in mind you may

need a little more engine power.

- Once the speed is below 100

knots, deploy one flaps step (]).

- Once an altitude of 500 feet

is reached, keep that

altitude.

Once a

flight speed of 70 knots is reached, keep that speed. (If in doubt,

keep above 500 feet.) The exact altitude doesn't matter much provided

it

is stable. But stick

to 70 knots.

- Control the

altitude using the engine. Add a

little engine power if you are too low (type a few Page Up), retract

a little power

if you

are too high (type a few Page

Down).

Allow

the altitude "plenty" of time to get right. No need to get exactly 500

feet or whatever altitude you choose, but try to keep it stable. (Be

foreseeing: add a little engine power even while the altitude

decreased only very slightly. Retract power even while the desired

altitude is not yet attained...) You need an engine RPM of

roughly 1,900. That's the minimum

of the

green zone right of the tachometer. This should keep you in a stable

horizontal flight at 70 knots, provided you lowered one step of flaps.

Do not try to tune in exactly

1,900 RPM. Tune what suits to keep a stable altitude... Try to

make frequent little tunings, instead of seldom heavy tunings. Try to

foresee what is going to happen. Best is to add or retract a little

power in advance.

- Tune the trim to get the average position of the yoke/elevator

centered. This is not mandatory on the simulator, yet that way you

better mimic piloting a real airplane. On the Cessna 172p (with no

load) this means trim on neutral.

- Be firm

with the flight speed. Keep a tight and quick control on the yoke/mouse

to keep 70 knots. If the speed is lower than 70 knots, push the yoke to

gain speed (no matter you lose altitude). If you are above 70 knots,

pull the yoke to lose speed (again, no matter this makes you gain a

little altitude). Don't panic if the speed rises to 75 knots or

decreases to 65 knots. But keep in mind you can really get in trouble

if you approach a short runway at 80 knots. I manage to keep the speed

between say 68 and 72 knots.

- Fly at constant speed and

steady altitude towards

the runway. 70 and 500. Keep trying to align

with the runway. You will *never* be perfectly aligned. You have to go

on aligning till the airplane halts on the runway...

- Now you are at a low flight speed of 70 knots, no

more use the ailerons/yoke to turn. Instead use the ailerons to keep

the wings horizontal. Turn using the rudder (Keypad keys 0 and Enter). The rudder can seem an odd

device for this purpose yet you will get used to it. Move the rudder

only a few key hits to the right or to the left. Be patient. Make one

key hit at a time and allow the airplane to stabilize before you

possibly make another key hit. (When I started making landings, I found

the rudder to be hectic and I preferred to use the ailerons to turn. As

experience build up, I finally found out that turning with the rudder

allowed for more precise and comfortable adjustments.)

- The airplane may oscillate a

little. Don't bother. Just

keep in

control using the yoke.

- You're flying at constant

altitude and 70 knots speed. Once the beginning of

the runway passes under the engine

cover, it's

time to take things up seriously. This is shown in the picture below.

(Whatever altitude you are flying, once the engine cover begins to eat

the runway, you are at a correct angle towards the runway start.)

- Type ]

two times, to

deploy the full three flaps steps.

- Immediately push the yoke

forwards, to make the airplane plunge to the ground. Indeed, the full

flaps deployed make the plane brake. You plunge towards the runway to

land, of course, but also to keep the speed at 70 knots.

- Decrease the engine power. 1/4 the maximum is often fine. The

Cessna 172p needs even less. I tend to decrease the engine power

throughout the dive, to end with almost no power. The possibility to

add engine power is necessary for your safety and for the precision

of the landing, but also the possibility to decrease the engine power.

So I try to make my dives a way that I keep the engine at some decent

power level throughout the dive. If a dive obviously begins with the

need to decrease the power to minimum, there is a risk you touch the

runway far beyond its start.

- Watch the

speed

indicator like it if was your heartbeat. Control the speed using the

yoke/elevator.

- The dive makes you head

towards the runway. You will

soon

become aware that the plane is going towards a point of the runway

much further than the start of the runway. There is nothing

wrong

with that on a long runway. Yet you should train to land on short

runways. In order to correct the dive and head towards the start

edge of the runway, decrease the engine power. (On the Cessna 172p

this often leads to power to minimum, while on most other airplanes

you keep some power tuned in.) The picture below is a snapshot

from a

good dive. (Note the vertical speed indicator shows -500 feet/minute. I

never use that indicator. I solely aim at the runway edge and

its 12 white strips. Anyway, -500 feet/minute is the right descend

speed...)

- Closely keep the speed at 70

knots by pulling and pushing

the

yoke. Calmly increase and decrease the engine power in order to

head the

plane towards the starting line of the runway. Don't bother to aim

exactly

at the start of the runway. It doesn't matter if you arrive a few feet

before the runway start or much further after it. Provided

you arrive at

70 knots.

- Keep aligning with the runway, using the rudder pedals

to turn (keypad keys 0

and Enter). Keep the

wings level with the horizon using the mouse/yoke/ailerons. (Use the

ailerons

to turn only if an emergency occurs and you need to make fast and steep

turns. Then you probably need to abort the landing and get back to

altitude (see below).)

- If you suddenly realize you will arrive

really far before the

beginning of

the runway, possibly retract the flaps to one step ([). You can also let

the engine roar to maximum power for a few seconds. If you followed the

procedure you shouldn't need to do such extreme things... (At any time,

if you feel

things are going wrong, retract the flaps to one step, throttle

to full

engine power, put the trim on

neutral and gain back altitude

(keep the

speed above 70 knots). Whatever wrong happens -- you arrive aside from

the

runway, too far before the runway, at a wrong speed, a swarm of birds

is passing, whatever -- abort the landing. Get back

to altitude and

retry.)

- The "rounding" is the most

impressive part. You are like

going to

crash on the runway. Yet you will pull the yoke/mouse

before it's too late. Don't pull on

the yoke too

early. Don't pull on the yoke too firmly. Once you are really close to

the runway (for a beginner: once you are convinced it's too late and

you are going to smash into the ground), pull the yoke gently and

bring the plane in a steady flight above the runway. That's the

rounding. (During the rounding, ground effect

contributes to your security

and ease.)

- It is often best to reduce the engine power to minimum during the

rounding.

- Go on using the rudder

pedals (keypad 0

and keypad Enter)

to keep aligned with the

runway. Use the yoke/ailerons to keep the wings level with the

horizon (so both left and right wheels will touch the runway at the

same

time).

- Now you're flying close

above the runway (in ground effect). Throttle the engine

power to

minimum if it wasn't already done (this is mandatory). Deploy full

flaps if they weren't already

deployed completely (this is not mandatory on a long runway). (Don't

shut the engine down. Just throttle to minimum power. It still can

happen that you suddenly must take off again and need full power in a

few seconds.)

- Keep the plane flying close

above the runway. As the speed

decreases

from 70 knots down to 50 knots and below, keep pulling more and more on

the

yoke/mouse, steadily. Keep the plane in

the air while ensuring it stays really close to the surface of the

runway. Steadily lift the nose, while the plane slows down, up to quite

a strong angle. Make sure

the plane does not gain back

altitude (don't look at the

instruments, look at the outside). You

really have to avoid the plane rises back in the air. Indeed it would

do that at a speed below

70

knots... (You shouldn't need to pull the yoke

more than 1/2 its maximum.)

- Don't land the plane. Let it land by itself, once the speed is

too

low and the nose is high up in the air. The plane renounces to

fly, it calmly sinks in and the two rear wheels touch the runway. If

you don't hear the wheels hit the runway and the wheels

nevermore leave the runway, you probably made an optimal landing. This

also makes the

front wheel stays above the runway while the two rear wheels touch.

- Once the rear wheels roll on the runway, retract the flaps. That

way the wings will lift less and the plane will be more firmly on the

ground. (My favorite way to land the airplane is to let the flaps down

and keep pulling on the yoke while the airplane is rolling. That way I

get maximum braking. I suppose this is an example of the difference

between a simulator and reality. Using my way the airplane risks to get

back in the air any moment and it is very sensitive to blows of wind.

If I made real landings, maybe I wouldn't dare do this...)

- When the plane is rolling, an optimal position for the

yoke/elevator seems to be pulled 1/2 of the total way.

- Use the rudder pedals to keep the

plane rolling in the middle of the

runway

and straight while the speed decreases. This most often leads me to two

keypad Enter hits to the right

of the center position.

- Once rolling at a speed below 40 knots, the nose will go down

automatically. Help it by pushing

the yoke/mouse calmly, back to neutral position. The front wheel now

must touch the runway.

Beware: check the rudder position first. If it is

too much to the left or to the right, the plane will turn violently

once the front wheel touches the runway. The plane may even fall aside

and

hit the ground with a wing tip. (The rudder slightly to

the right; two keypad Enter

hits, seems an optimal position.)

- Now the front wheel is on the ground, use the mouse to control

the rudder. Keep the left mouse button down and forget the keypad keys.

Maybe just check the ailerons and elevator positions are sound before

you press the left mouse button. (Actually if everything went correctly

and there is no crosswind, you shouldn't need to steer the plane using

the rudder.)

- Once the front wheel is on

the ground, you are allowed to

use the brakes. Your choice. Keep the b

key down. Be

prepared to release it should a problem occur.

If you forgot to almost center the rudder, braking can go really bad.

Once the plane is halted or at very low

speed, you can release the b

key (if you used

it) and add a

little engine power to taxi to the parking or hangar.

To shut the engine down:

- Engine throttle to

minimum (hold Page Down

down for a

while).

- Pull the mixture lever to

halt the engine (mouse in normal pointer

mode, click on the left of the red mixture lever to pull it

out).

- Rotate the magneto switch to

OFF (a few hits on {).

To set the parking brakes in, type B.

You must be mentally prepared to abort

landing

anytime. Whatever happens: an order from the control tower, a wrong

speed or landing angle, a wrong alignment with the runway, a strong

blow of wind, birds flying over the runway... retract the flaps to one,

push the engine to maximum, center the trim and get

back to high altitude. Then either you restart the landing

procedure or you go for another airport. The pride of a pilot is to

make only safe landings.

Don't try to find "the ideal distance" to start diving to the runway.

The procedure above proposes you start diving when the white engine

cover starts eating the runway edge (provided you fly at 70 knots with

one flaps step) (the altitude doesn't matter). Best is you train

to land while starting the dive earlier and while starting to dive

later. You need to be trained to increase or decrease engine power

according to what is needed. During a real landing, depending on the

airplane's weight, the wind speed and other random things, the "ideal"

moment to dive is unpredictable. As experience builds up, you will

better feel the right moment.

If you want to make things simple for your first landing trainings,

make use of the

fact the runway at

KSFO is very long. Wait a little more before you begin the dive: let

the nose "eat up" the whole length of the leading part of the runway

(let the successive pairs of white strips on the runway disappear below

the airplane nose). Then lower the flaps

to

three steps and decrease the engine to minimum. Dive to keep the speed

around 70 knots and try to keep aligned with

the runway. You will end the dive quite far beyond the runway

start and at a high vertical speed, but who cares. Make the final

rounding. Keep aligned with the runway and

try to fly close above it. Keep

pulling more and more on the yoke/mouse, to keep the airplane flying.

Yet avoid it rising in the air. Till the wheels touch the ground. Then

just keep the airplane on the runway, using the rudder. Once

the speed is below 40 knots, push the

yoke/mouse and keep key b down

to brake.

If you are a newbie, you probably won't succeed to apply the procedure

perfectly. My advice: invent your own, more simple procedure. Then

regularly come back to the procedure listed here and read it again, to

get hints and

ideas to better your procedure. Till you get it. Also best read other

landing procedures. Send me a mail if you find interesting differences.

Analyze your own procedure. If it implies to fly at very low speed, it

is dangerous because a blow of wind from the rear will make the plane

fall. A probable problem with your procedure is the plane needs a lot

of runway length to land. If you look at the runway start you will see

there are successive groups of white stripes. I land the Cessna 172

always well before the last group of

stripes. If you are a real beginner, your procedure surely will make

the

plane tilt over or crash once in a while. The procedure listed here is

safe.

Train your procedure, again and again. The more you train it, the more

you will become able to use the one listed here. That's the way I

learned to land...

!

In a real airplane, you

must keep in touch with the

control tower constantly while landing. You will be contacted by the

control tower or you have to contact it in some key parts of the

landing. If you don't contact the control tower just after landing, an

emergency rescue team is immediately underway. If there is no good

reason you didn't contact the tower, you will really be in trouble.

Maybe you'd like to train landing without having to take off

and circuit in order to head for the runway and land. Type the command

line displayed below in a terminal window to start the simulator in

flight and heading for the runway. The airplane is placed 6

miles ahead of the runway, at an altitude of 1000

feet and a speed of about 120

knots.

fgfs --offset-distance=6

--altitude=1000 --vc=120

Possibly add --timeofday=noon

--geometry=1024x768

parameters if you need daylight and a bigger window (choose anything

you

need instead of 1024x768 (I favor 1200x900 an my screen)). FlightGear

command

line parameters are listed in http://www.flightgear.org/Docs/InstallGuide/getstartch4.html#x9-330004.4

(Note the parameters above make the airplane have some trim tuned

in. Yet you need another trim tuning during the

horizontal steady flight towards the runway. See the chapter above,

about the trim. If

in doubt, just center the trim. On the Cessna 172p, a centered trim

seems the right position.)

Once you are trained, you no longer need to do a long horizontal flight

at 500 feet and 70 knots to get to the runway. Instead you can descend

all the way from your flight altitude and at a higher speed. You should

be able to get at 500 feet and 70 knots a short while before the final

dive.

Landing at 65 knots instead of 70 knots allows to use a much shorter

runway length. Yet to benefit from this you better train landing at 65

knots. It is quite different from landing at 70 knots.

The landing speed varies according to the load of the airplane. The

more load of petrol, passengers and freight, the higher the optimal

landing speed will be.

How to fly when there is wind

Think of a hot

air balloon. Think of it as being in the middle of a

gigantic cube of

air. The cube of air may move at high speed compared to the ground,

anyway the balloon

itself is completely static in the middle of the

cube. Whatever the wind

speed, persons aboard a hot air balloon

experience not the faintest blow of wind. (To pilot a hot air balloon

you bring it at an altitude where the wind blows in a direction that

more or less suits your needs.) The same way, an aircraft flies in the

middle of a gigantic cube of air and only refers to that cube of air.

The motion of the cube of air compared to the ground doesn't bother the

aircraft.

You, the pilot, on the contrary, do bother for the speed of the

surrounding air compared to the ground. It can make you drift to the

left or to the right. It can make you arrive at your destination much

later or much sooner than planed.

When the wind blows in the same direction as you fly, the speed of the

wind adds itself to the airspeed of the plane. Hence you move faster

compared to the ground. You will arrive earlier at your destination and

have less time to enjoy the landscape. (It sometimes happens that a jet

airliner flying with a strong wind from the rear, moves faster than the

speed of sound compared to the ground. Though it doesn't brake the

sound barrier.)

When the wind blows in the opposite direction you fly (towards the nose

of the plane), the speed of the

wind subtracts itself from the airspeed of the plane. Hence you move

slower compared to the ground. You will arrive later at your

destination and have more time to enjoy the landscape. (Some slow

airplane flying against strong wind can even seem to fly backwards,

because the speed of the wind is faster than the flight airspeed of the

airplane.)

The two cases above are quite simple. More complex is when the wind

blows towards the side of the airplane. Look at the pictures below.

- On picture (a) there is no wind. The pilot wants to reach the

green hill situated to the North. He heads for the hill, towards the

North, and reaches the hill after a while. When there is no wind, you

just head towards your destination and everything's fine.

- On picture (b), the pilot keeps heading to the North. Yet there

is wind blowing from the left; from the West. The

airplane drifts to the right and misses the hill.

- On picture (c), the pilot keeps heading towards the hill. This

time he will arrive at the hill. Yet the plane flies a curved path.

This

makes the pilot loose time to get to the hill. Such a curved path is

awful when you need to make a precise navigation. (Note something: the

airplane tends to get into the wind, like a weather vane.)

- Picture (d) shows the optimal way to get to the hill. The plane

is directed to the left of the hill, slightly towards the West. That

way it compensates the wind and keeps on a straight path towards the

hill. It will need more time to reach the hill than if there was no

wind, anyway this is the best attitude. (Note something: the solution

is to let the airplane head a little bit into the wind, like a weather

vane would.)

How much to the left or to the right of the object must you head? At

what angle? Serious pilots use tight geometry and trigonometry

computations to get near

exact and optimal angles. Yet I wouldn't fly a virtual Cessna 172p if I

had to

do such dry things. You need no computations at all to fly roughly

straight. The trick is you must keep your eyes on the object you fly

towards. You know you will head the plane in a direction to the left or

to the right of

the object, but you don't need to know the angle. Just keep your eyes

on the object. Get aware you are drifting leftwards or rightwards. Then

let your instinct slowly head the plane to the right or to the left to

compensate the obvious drift. When you begin

training this, you need to force your instinct a little bit and think

of what you are doing. Very soon this will become automatic, just like

when you learned to fly straight. You will no more keep the plane

headed towards the object. You will rather keep it flying towards

the object. The picture below shows a flight towards the top of the

little

mountain ahead. Wind blows from the right. I just look at he

mountain top. And I let my hands head the plane to right of the

mountain, without really thinking about it:

The faster the flight airspeed compared to the wind speed, the less the

wind will influence.

How to take off when there is wind

Main recommendation to take off is you must find a way to accelerate

facing the wind; with the wind blowing towards the nose of the

airplane. Before most

runways are build, statistics are made about the wind at that location.

The runway orientation is chosen so it aligns with the wind most

often. Lots of airports

have two runways at different orientations

because the wind sometimes blows in one of these directions and

sometimes in the other direction. The location of an airport is often

chosen because at that place the wind often has a stable direction and

speed.

Take off with a faint wind blowing towards the rear of the airplane,

say 1 knot, for sure

is no problem. Yet above a few knots you can get into trouble. With a

10 knot wind blowing from the rear, the front wheel will rise at the

usual 40 knots airspeed, but that makes 50 knots compared to the

runway. What matters is the speed the front wheel roll over the runway,

not the airspeed... If a problem occurs and you are still rolling at 60

knots on the runway, the consequences will be more dramatic. To end

with, you will need much more runway length and have less opportunities

to abort the landing.

The main way to know the wind direction and speed is to go to the

control tower or ask the control tower by radio. A necessary and

complementary tool are the windsocks at both

ends of the runway. They show the wind direction

and speed. The longer and the stiffer the windsock, the more wind there

is. The windsock on the picture below shows an airspeed of 5 knots:

So, you have to choose a runway start that allows you to

take off with the airplane facing the wind. In real life you are not

always allowed to do this. Either there is no runway aligned with the

wind or the control tower tells you to use another runway. Then you

have to take off under crosswind; the wind blowing towards a side of

the airplane.

Basically, you can use the exact same procedure as listed above for a

take off when there is no crosswind. Yet you have to be aware of

several important facts listed below. To train this, start FlightGear

with the parameter --wind=0@10

which implies a wind of 10 knots blowing from the North (direction 0).

If you take

off from the usual San Francisco KSFO airport heading to the West, this

makes the wind blow from the right.

- You will have to push the rudder at quite a strong angle to stay

rolling aligned with the runway. Keep the rudder at that angle once the

front wheel leaves the ground and a little later once the rear wheels

leave the ground.

- Say the wind is blowing from the right. You would think you have

to push the right rudder pedal, to head the airplane a little bit into

the wind, to compensate for the leftwards push of the wind. Well you

have to do the exact opposite: push the left rudder pedal. This is

quite unnatural yet that's life. The reason of this is the rear

vertical stabilizer is pushed by the wind leftwards. The plane reacts

like a weather vane and heads in the wind. The plane as a whole turns

to

the right, with quite a strong force. You have to compensate by pushing

the rudder to turn to the left. So, you take off with the ruder pedals

pushed to the left. The picture below shows a rudder angle during a

take off with a 10 knots crosswind blowing from the right:

- The airplane will tend to bank leftwards. Hence you will have to

push the yoke/ailerons to the right. Actually you best place the yoke a

little to the right before the wheels start leaving the ground. (Best

is to push the yoke to the right from the start on. Indeed this is the

best way to taxi safely under a crosswind blowing from the right.) The

picture below shows an appropriate yoke/ailerons position, while

taking off with that 10 knots crosswind blowing from the right.

- The airplane will rise in the air much slower. The vertical speed

will be quite weak. This is because the rudder is at a a strong angle.

The airplane moves through the air with its right flank and brakes. You

have to wait till the rudder is centered before you get the regular

vertical speed. Center the rudder very slowly, a little angle step at a

time. Meanwhile, using the yoke/ailerons, gradually head the airplane a

little bit in the wind, to keep flying aligned with the runway. Wait

till you are above a few hundreds feet before you start centering the

rudder.

Why do you keep the yoke to the right and the rudder pedals to the left

once the airplane rises in the air? This can seem odd. It's quite

logical that way the airplane will fly straight. The ailerons and the

rudder compensate each other and the airplane turns neither to the

right, neither to the left. But again, why do this, why not simply let

the yoke/ailerons and the rudder centered? The airplane will fly

straight too and be far less braked. The reason why we do this is the

ailerons keep the airplane banked to the right; towards the direction

the wind is blowing from. Hence, the huge force on the wings, that

keeps the airplane in the air, that huge force is now slightly directed

to the right. In normal circumstances this would make the airplane move

slowly sideways to the right, at 10 knots speed... Currently, it

compensates for the 10 knots wind and keeps the airplane above the

runway. So despite the wind, the airplane stays headed towards the

runway end and stays above the runway middle. Everything's fine (except

for the braking).

To me, 10 knots wind is a maximum to take off the Cessna 172p safely.

How to land when there is wind

You land the Cessna 172p under crosswind the same way you take off:

- Try to land with the wind blowing towards the airplane face. Bear

in mind the wind blows the airplane away from the runway start. So

start the dive later, when the engine cover already ate some length of

the runway.

- Under crosswind, use the exact same rudder and ailerons tuning as

for take off under the same crosswind. Train this by taking off and

landing under crosswinds. When the wheels leave the ground

and you find the appropriate yoke/ailerons angle, note down the rudder

angle and the yoke/ailerons angle. Center the rudder and ailerons

during the flight and make a circuit to land back. During the landing,

when you fly at constant 500 feet altitude and 70 knots speed, knowing

the crosswind is the same, tune in back the rudder and ailerons angle

that where optimal during take off.

Under high crosswind, hence with a strong rudder angle, the plane

brakes a lot. This implies two things:

- During the approach to the runway, at constant 500 feet altitude,

70 knots speed and 1 flaps step, you need much more engine power to

keep the altitude stable.

- Once you dive towards the runway start, keep in mind the plane is

braking. So you don't need to deploy additional flaps steps. Just

decrease the engine power.

Landing that way is quite comfortable, despite the crosswind. You just

have to be a bit more careful with the rudder once the airplane rolls

over the runway. And best keep the ailerons as if turning towards the

wind.

Note such a landing, with a steady crosswind, is unrealistic. In the

real world the wind varies quickly. You get sudden increases and gusts

of wind. The control tower just tells you by radio the maximum speed of

the

gusts. You have to adapt constantly during the landing, to

react to the turbulences and gusts.

As for the take off, 10 knots wind seems a maximum to me. (Should you

ever have

to land under heavy wind, say 25 knots or more, and there is no runway

aligned with the wind, maybe best don't land on the runway. Or don't

try to align with the runway. Align exactly with the wind and make use

of the fact you need less ground length to stop. When the plane is

going to stop keep the rudder pushed. Don't try to taxi. Simply push

the parking brakes in, push the trim and get help to latch the airplane

to the ground. In fun mode, landing the Cessna 172p under 70 knots wind

is great. You simply let it descent to the ground vertically. This is

quite unrealistic because at such a wind speed there are tremendous

turbulences close to the ground.)

The technique described here is the slip landing.

Another crosswind landing technique is the crab landing.

How to taxi when there is wind

Under 10 knots wind the Cessna 172p seems not to need particular

precautions when taxiing. Yet any sudden increase in wind speed can

tilt it and tumble it over. So best apply the recommendations whenever

there is wind.

To train taxiing on the ground when there is wind, ask for a strong

wind like 20 knots. Such a wind can tilt the plane and blow it away

tumbling any moment. One single error during taxiing and the plane is

lost.

Main rule is you must push

the yoke towards the wind. This deserves some physical

explanation:

- When the wind is blowing from 12 o'clock, this is quite logical.

The yoke is pushed (towards 12 o'clock) and the elevator makes the tail

rise a little. That's the most stable position to avoid the plane be

tilted by the wind.

- When the wind comes from 10 o'clock, pushing the yoke towards 10

o'clock makes the elevator is close to centered. The elevator almost no

more trades in. Now the most important part is played by the ailerons.

The left aileron is upward and the right aileron is downward. This

pushes the left wing down and lifts the right wing. Again, that's the

most stable position to avoid the plane be tilted by the wind.

- When the wind blows from 8 o'clock, you would think you should

invert the position of the ailerons, to keep the left wing being pushed

down. Hence you should push the yoke to 4 o'clock. Wrong! Keep pushing

the yoke to 8 o'clock. The reason is the downward position of the

aileron on the right wing makes it act like a slat. This increases the

lift on the right wing and this is all we want. Symmetrically, the

upward position of the left aileron decreases the lift of the left wing.

- When the wind comes from the rear, from 6 o'clock, the yoke is

pulled (towards 6 o'clock). The upward position of the elevator tends

to make the tail be pushed down. Once again this is the best. Strong

wind can push the tail against the ground. This is impressive but the

tail is conceived to withstand this.

Accept the plane nose can be tilted and the tail pushed against the

ground. Keep cool. This can be impressive yet there is nothing

dangerous with it. Go on using the brakes, rudder and engine to move

the airplane.

If you want to move towards the wind, you will need more engine power.

When the wind blows from the rear you may need no engine power at all.

Always keep the engine power to the minimum needed.

Especially when turning, move very slowly. Make little changes at a

time. Take your time and closely survey the yoke angle. Constantly keep

it pushed towards the wind. Constantly try to reduce the engine power.

Keep in mind using the brakes too firmly may shortly tilt the plane at

an angle that allows the wind to tilt it and blow it away.

The autopilot

An autopilot is

not an "intelligent" pilot. It just takes over simple and wearing parts

of your

work as a pilot. You still are the sole real pilot aboard and have to

keep aware of everything. Be prepared to shut the autopilot down.

During take off and landing, relying on the autopilot would be

suicidal, because you have to keep an immediate control on every

function of the airplane. (Dumb autopilot systems are reported to cause

less accidents than smart ones with artificial intelligence inside.)

The autopilot is that little rack to the right of the yoke:

Switch it on by pressing its AP button

(standard mouse mode). The autopilot then controls the roll. It keeps

the wings level with the horizon. This is displayed in the picture

below by the "ROL"

marking. To switch the autopilot down press again on AP.

If you press the HDG button

the autopilot will try to keep the plane flying towards the direction

tuned on the directional gyro by the red marking (see the chapter about

direction). "HDG"

stands for "heading". Press again on the HDG button

to get back to roll control mode (or AP to

switch the autopilot down).

The buttons ALT,

UP and

DN are

used to tell the autopilot either to control the vertical speed (VS)

or the altitude (ALT).

From here on you maybe better study the document used by the author of

the autopilot system in

FlightGear: https://www3.bendixking.com/servlet/

com.honeywell.aes.utility.PDFDownLoadServlet?FileName=/

TechPubs/repository/006-18034-0000_2.pdf

Security

Security is first of all a matter of common sense. Avoid to land with

the landing gear retracted. Fill the reservoirs before take off and

don't let them get empty in flight. This may seem funny

recommendations,

the fact remains I made several landings on the aircraft belly when I

started using the flight simulator. I got angry on myself and now it

nevermore happens that I forget such a simple and essential thing. In

real life you are not allowed to land airplanes on the belly in order

to get angry

on yourself. I suppose it is a part of the role of the monitors to make

you feel the angriness *before* your first solo landing. I suppose they

don't let somebody fly on his own till they feel the angriness is

rooted deeply enough in him. People who cannot cope with this are not

meant to become pilots.

There are many more vital details than the landing gear and the fuel.

That's why checklists exist. There are checklists for

all kinds of normal or emergency situations. There are long checklists

and short checklists. This link provides checklists for the Cessna

172p and for other airplanes: http://www.freechecklists.net

. Those checklists refer to much more levers, buttons and triggers

than talked about in this tutorial. There is nothing complicated in

those checklists provided you learned what all those little things

are. For example one item is you have to verify the seats backs are

upright.

You have to learn to cope with stress. Wherever I get access to

computers I try to install FlightGear. To me the computer industry

should focus solely on building computers for FlightGear. Secondary

tools like browsers, mailers, spreadsheets and the like, should be

regarded as optional sub-functions of FlightGear. Once the installation

is finished, I make a demo flight. Strangely, most people simply don't

care about what I am doing. They just go on talking, asking questions,

requesting my attention... What's more I'm often not in the most

adequate position toward the screen, the keyboard and the mouse. It

becomes almost impossible to fly correctly, especially to land.

Basically there are two possible attitudes. The first one is I get

silently angry on the disturbing persons, I stop the demo and I

consider it's their fault if I cannot succeed my flight. The second

attitude is I breath deeply and calmly, I find ways to go on managing

the burdens and the problems, I don't get angry on anybody, I claim

nothing to be responsible for anything, I renounce to make a perfect

demo flight and I focus on making a mediocre yet secure landing. The

advantage of the first attitude is that you feel comfortable about your

superiority on FlightGear-unaware persons. The disadvantage of the

second attitude is that you

have to endure the humiliation of an ugly landing and the people around

going on talking and requesting your attention. The advantage of the

second attitude is that in real life, on a real airplane, it allows you

to stay alive.

Communication is a basis for security. That means communication with

the

technicians, with the control tower, with your copilot, with the

passengers and especially with yourself. You have to constantly gather

data about the traffic, the meteorology and the state of mind of your

passengers. You have to constantly inform the control tower and obey

the instructions it sends you in return. You have to keep your

passengers in an acceptable mood and at the same time you have to

obtain they let you focus on your tasks when this is necessary. Lots of

airline accidents

occured because of a lack of communication between the pilot and other

crew members. That has been called "the Superman syndrome". Once the

problems start, the pilot focuses on his way to solve the situation.

Either the copilot does not understand what the pilot is doing or he

becomes aware of a danger the pilot did not realize. This results in

contradictory commands sent to the airplane controls, shouting, up to

fist fighting... till the final crash of the airplane. An important

part of the training for modern pilots is to learn to communicate with

the other crew members under high stress. They learn to go on

communicating and how to do that a short and efficient way. (I was once

told this anecdote: a monitor and a trainee were performing landings.

The trainee was a strong guy with muscles like truck tires. At one

moment the landing path appeared to be wrong. The monitor asked the

trainee to release the commands so he could take them over. There is

nothing wrong with failing a landing. Monitors themselves sometimes

fail a landing, abort and restart a new landing. But the trainee

panicked and crispated his hands on the yoke. The monitor could do

nothing. The consequence was a damaged landing gear.)

There is no room for luck in real aviation. When you train to become a

pilot, almost every possible situation is put into practice at least

once. For example a monitor makes you take off with a heavily loaded

airplane and suddenly shuts the engine down. You have to train to fly

and

land with a random airplane control or indicator out of order.

FlightGear

allows to reproduce some of these trainings. You can request

flight instrument failures using FlightGears' menus or command options.

A really bad

instrument failure means the instrument still

seems to operate correctly. Yet it doesn't, and what it does or

displays endangers you. While training you can decide to no more use a

given instrument or control. For example you can glue a

sticker on your screen to hide away an instrument. Best is you ask a

friend to configure a failure without you knowing what he did.

This heavy training and the numerous

precautions and rules are the reason why so few accidents occur. In

most cases, even a severe problem does not lead to an

accident. Accidents are often due to the unlucky addition of several

different problems.

The picture below shows the artificial horizon indicator. I hardly

never use it. I fly looking at the real horizon. Anyway the artificial

horizon saved me more than once on the simulator. When you penetrate by

mistake in a cloud or a bank of mist, you suddenly get a white outside.

There is no more way to keep the plane flying level, except by using

the artificial horizon. You may argue this is due to the lack of

feedback

own to the simulator. You're (dead) wrong. The same problem occurs on a

real airplane. Quite many of the (very few) accidents in little

airplanes

like the Cessna 172 or the PA-28 happen that way. It is prohibited for

a pilot with no IFR license to enter a cloud. Some do it anyway. Or

they get caught in a rise of mist the control tower didn't warn for.

The airplane banks and in

two minutes time it goes flying upside down. The pilot

is unaware of this. Even worse: some instruments seem to get mad, with

no obvious reason. A crash is unavoidable. I learned the reflex

to focus on the artificial horizon, the altimeter and the directional

gyro. When this happens the plane is often already severely banked. I

keep calm and I use the instruments to maintain the plane in a sound

flight.

It will oscillate a lot but serious problems will be avoided. Either I

will wait till I get out of the cloud or I will gain or loose altitude

to get out of the cloud layer. I strongly advice you train this using

the simulator. Best is you make a complete IFR training.

One thing you have to train for your security is landing on very short

distances. Some flight incidents, like an engine failure or a sudden

change in the weather, can force you to land on the first strip of flat

land you encounter.

The HUD allows to fly and land more easily, with less stress. It also

allows to optimize what you are doing and this is good for security.

For example it allows to touch the ground very close after the

beginning of the runway. That way you have the whole length of the

runway to brake. (A HUD is available for every aircraft on FlightGear,

even the 1903 Wright Flyer. In real life, few little civil airplanes

contain a HUD. It is too expensive and too recent.)

There are some strong differences between a flight

simulator

with minimalistic control hardware and a real airplane. The fact the

mouse exerts no counterforce, the

fact you don't feel the vibrations and forces inside the airplane... On

one hand, some aspects of flying are made easier on the simulator.

On the other hand, a real airplane constantly gives all sorts of

valuable feedback you don't get with a simulator. One thing is common

to

the simulator and the real airplane: while landing you'd wish you had

four arms and two more brains.

FlightGear contains bugs. Consider those problems as a training for

real aircrafts.

Problems on real aircrafts are not the same. But there are problems.

When FlightGear suddenly puts you in a critical situation due to a bug,

consider this as a training. Try to solve the situation fast and

efficiently while keeping calm. It's not a bug, it's a feature!

The handbooks of airplanes contain procedures and checklists for

emergency situations. It sometimes happens that the adequate reaction

to

a problem is exactly the opposite for two different airplanes. That's

one reason airline pilots are not allowed to fly different airplanes at

the same time. If they choose to go flying another type of airliner,

there are imposed to stop flying for a lengthy period, during which

they will practice the other type of airplane on simulators. The wide

range of aircrafts available under FlightGear allows you to experiment

with this.

How to land the Cherokee Warrior II

To write this chapter I just gathered some data about the Cherokee

Warrior II and I made experiments with FlightGear. Don't consider this

as a tutorial but merely as hints to toy with the virtual Cherokee

Warrior II.

On Linux you get the

Cherokee Warrior II (or PA-28) with the --aircraft=pa28-161

command line parameter. The Cherokee Warrior II has some

advantages upon the Cessna 172p. Thanks to its low wings it is far less

sensitive to crosswind. Fully extended flaps are more braking and

allow to land on a much shorter distance.

Take off is the same as for

the Cessna 172p (in FlightGear. In real life their take off checklists

are not exactly the same).

You have to get

used to some minor differences of the Cherokee Warrior II for the

landing:

- During the steady horizontal flight before landing, the trim must

be pulled a little below neutral in order to get the yoke oscillating

around neutral.

- The optimal tachometer RPM during landing is at a lower RPM than

the tachometer green zone. Roughly, keep the needle vertical.

- Only put one more flaps step (which makes two flaps steps

deployed) when the dive towards the runway begins. Don't decrease the

engine throttle too much.

- If you keep it to two flaps deployed during landing, the hover

above the runway

and the final roll will be similar to the Cessna 172p. Yet if you

put the third flaps step in (after the final

rounding), the plane will brake firmly. It will very quickly touch the

runway then come to a near halt. Be prepared to lower the front wheel

very soon. (It is possible to use the third flaps step during the dive

towards the runway, instead of tuning the engine power down.

Oscillating between two steps and three steps allows to aim the runway

start. Yet keep two flaps steps and tune the engine seems

easier.

An interesting stunt is to fly stable till nearly above the runway

start, then tune the engine to minimum and deploy three flaps steps.

The

plane almost falls to the runway. It's impressive but it works.)

In real life, an advantage of the Cessna 172p upon the Cherokee

Warrior

II is the fuel reservoirs of the Cessna are located in the wings close

above the center of the plane and higher than the engine.

What's more an automatic system switches between the reservoirs. That

makes you almost don't have to bother for the way the fuel gets to the

engine in flight. On the contrary, on the Cherokee Warrior II the

reservoirs are located separately, on both wings and lower than the

engine. That means you have to constantly switch between the two

reservoirs in flight. Should one reservoir become much lighter than the

other, this would destabilize the airplane. The fact the reservoirs are

lower than the engine means you have to control the fuel pumps and the

backup fuel pumps.

Some links:

How to take off and land the Piper J3 Cub

Use the --aircraft=j3cub

parameter to get the Piper J3 Cub on Linux.

The Piper J3 Cub

is a very different airplane from the Cessna 172p and

the Cherokee Warrior II. The Cessna 172p and the Cherokee Warrior II

are front wheel airplanes while the Piper J3 Cub is a tail wheel

airplane. Stall speed seems to be a little below 40 mph

(the Piper Cub's airspeed indicator is in mph) (remember the HUD

expresses speed in knots, not mph). I

guess an appropriate speed to rise in the air is about 60 mph. Normal

flight speed seems about 80 mph.

It is a simpler aircraft, as it has no flaps and few instruments. This

doesn't mean it is easier or safer to fly. While you will find the

"three points" take off and landing to be quite easy in FlightGear, the

"two points"

take off and landing need serious training. You need to master these

procedures (and many others) to fly the Piper Cub securely. Worst that

can happen is you

get confident in the airplane without having been trained to the

numerous possibilities of things going bad. Then you simply won't be

able to prevent things to go bad. (And, again: you're reading a

tutorial

written by somebody who has no pilot license and who never even flew a

Piper Cub as a passenger.)

This is what I believe to be the "three points" take off. It is quite

simple to perform in FlightGear, but: a friend who is a pilot told me

he learned this procedures much later than the "two points", because in

the real world the wind makes the three points procedure difficult. It

can be performed

in FlightGear without using the rudder, which of course is not

realistic:

- You need the simplified

HUD (h h I), just to know the yoke and throttle positions.

- Fully pull the yoke backwards and keep it there.

- Throttle the engine to maximum (Page Up).

- Once

the

front wheels clearly rise from the ground, slowly push the yoke back

to

neutral,

towards a

normal flight close above the runway (the pushing takes about a lengthy

second).

- Let the plane accelerate to 60

mph, then pull the yoke and keep about 60 mph while rising

in the air.

- Once you got to 500 feet, push the yoke to stabilize.

- Keep 500 feet. This will bring the speed to about 80mph.

Meanwhile make a 180° turn to go for the landing. Fly a long time, till

the runway is a good distance behind you,

then make another 180° turn to head for the runway.

This is my favorite three points landing:

- Keep the 500 feet altitude and about 80 mph speed; don't reduce

the engine power.

- Look for some obvious ground features far to the left and to the

right of the start of the runway. You will need them shortly.

- Once the top of the yellow motor cover touches the runway start,

things become tight. Go on flying straight till the runway start is

going to match with the top of the instruments on the instruments

panel. As the instruments panel is not transparent, you cannot check

for this directly. But you can look at the ground features aside from

the runway.

- Pull the engine throttle to the minimum (Page Down). Begin

to push the yoke,

to ensure the speed won't go below 60 mph.

- Aim at the runway start with the top of the engine cover.

Meanwhile the speed will decrease from 80 mph to somewhere around 60

mph. Maybe a little more, maybe a little less, but it should stabilize

close to 60 mph, while you just keep aiming at the runway start with

the top of the yellow engine cover. You just have to "yoke" the

airplane towards the runway start, just making the top of the engine

cover match with the runway start. Don't use the throttle, just leave

the engine at minimum power.

- Once close to the runway, begin the rounding. Gently pull the

yoke. Not too much.

- Steadily pull on the yoke to keep the airplane above the runway.

The more it slows down, the more you have to pull on the yoke to keep

it from touching the runway. Best let is descend very close to the

runway. If the wheels touch the runway before the yoke is completely

pulled in, don't bother for this short touching, just pull a little

more on the yoke to rise again a few inches above the ground.

- Once the yoke is completely pulled in, the airplane will gently

fall on the runway.

- Once it rolls on the runway you can use the brakes to come to a

halt (b). The yoke must stay

pulled in completely.

Now, about what seems the "two points" take off. It more ressembles

that of a "normal"

airplane yet with

some big differences on the yoke:

- Push the left mouse button in and keep it pushed, so the mouse

now controls the rudder.

- Push the engine throttle to the maximum.

- While accelerating, more or less keep the plane aligned with the

runway using the mouse/rudder. This is the most difficult part of the

game. One tip is

to

stop aiming the rudder to say the left already when the plane just

starts to turn to the left.