An epicyclic train is often suitable when a large torque/speed ratio is required in a compact envelope. It is made up of a number of elements which are interconnected to form the train. Each element consists of the three components illustrated below :

|

|

We shall examine first the angular velocities and torques in a single three-component element as they relate to the tooth numbers of central and planet gears, zc and zp respectively. The kinetic relations for a complete epicyclic train consisting of two or more elements may then be deduced easily by combining appropriately the relations for the individual elements.

All angular velocities, ω, are absolute and constant, and the torques, T, are external to the three-component element; for convenience all these variables are taken positive in one particular sense, say anticlockwise as here. Friction is presumed negligible, ie. the system is ideal.

Separate free bodies of each of the three components - including the torques which are applied one to each component - are illustrated in Figs 2a and 2b for the external and internal central gear arrangements respectively. Also shown are the shaft centre O and axle A, the radii Rc & Rp of the central and planet pitch cylinders, the radius of the arm Ra.

There are two contacts between the components :

With velocities taken to be positive leftwards for example, we have for the external central gear :

and for the internal central gear :

Substituting for Ra from the geometric equations into the respective velocity and torque equations, and noting that Rc/Rp = zc/zp, leads to the same result for both internal and external central gear arrangements. These are the desired relations for the three-component element :

( 2a)

( ωc - ωa ) zc +

( ωp - ωa ) zp

= 0

( 2b)

Tc / zc =

Tp / zp =

-Ta / ( zc + zp )

It is apparent that the element has one degree of kinetic (torque) freedom since only one of the three torques may be arbitrarily defined, the other two following from the two equations ( 2b). On the other hand the element possesses two degrees of kinematic freedom, as any two of the three velocities may be arbitrarily chosen, the third being dictated by the single equation ( 2a).

From ( 2b) the net external torque on the three-component element as a whole is :

ΣT = Tc + Tp + Ta = Tc { 1 + zp / zc - ( zc + zp )/zc } = 0

which indicates that equilibrium of the element is assured.

Energy is supplied to the element through any component whose torque and velocity senses are identical. From ( 2) the total external power being fed into the three-component element is :

ΣP = Pc + Pp + Pa = ωcTc + ωpTp + ωaTa = Tc { ωc + ωp zp /zc - ωa ( zc + zp )/zc }

= Tc { ( ωc - ωa ) zc + ( ωp - ωa ) zp } / zc = 0

confirming that energy is conserved in the ideal element.

In practice, a number of identical planets are employed for balance and shaft load minimisation. Since ( 2) deal only with effects external to the element, this multiplicity of planets is analytically irrelevant provided Tp is interpreted as being the total torque on all the planets, which is shared equally between them as suggested by the sketch here. The reason for the sun- and- planet terminology is obvious; the arm is often referred to as the spider or planet carrier.

Application of the element relations to a complete train is carried out as shown in the example which follows. More complex epicyclic trains may be analysed in a similar manner, but the technique is not of much assistance when the problem is one of gear train design - the interested designer is referred to the Bibliography.

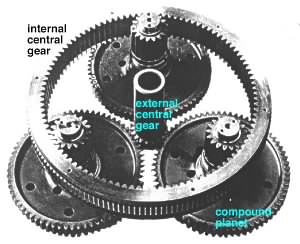

An epicyclic train consists of two three-component elements of the kind examined above. The first element comprises the external sun gear 1 and planet 2; the second comprises the planet 3 and internal ring gear 4. The planets 2 and 3 are compounded together on the common arm axles.

Determine the relationships between the kinetic variables external to the train in terms of the tooth numbers z1, z2, z3 & z4.

The train is analysed via equations ( 2) applied to the two elements in turn, together with the appropriate equations which set out the velocity and torque constraints across the interface between the two elements 1-2-arm and 3-4-arm.

Solution :

The basic speed ratio, io, of an epicyclic train is defined as the ratio of input to output speeds when the arm is held stationary.

Neither input nor output is defined here - indeed this terminology can be confusing with multiple degrees of freedom - so for example select gear 1 as input, gear 4 as output.

It follows that io = ( ω1/ ω4 )ωa=0.

Solving the three velocity equations and the six torque equations leads to the desired relations :

Velocities : ( ω1 - ωa ) = io ( ω4 -ωa ) where io = - z2 z4 /z1 z3

Torques : T1 = -T4 /io = Ta /( io - 1 )

Evidently this train possesses the same degrees of freedom as an individual element.